This is a guest post by Christian Eisold from berns language consulting. For many who have been using MT seriously already, it is clear that efforts made to implement the use of the correct terminology are a very high-value effort, as this is an area that is also problematic with a purely human translation effort. In fact, I believe that there is evidence that suggests MT (when properly done) outputs much more consistent translations in terms of consistent terminology. In fact, in most expert discussions on the tuning of MT systems for superior performance, there is a very clear understanding that better output starts with work focused on ensuring terminological consistency and accuracy. The way to enforce terminological consistency and accuracy has been well known to RBMT practitioners and is also well understood by expert SMT practitioners. Christian provides an overview of how this is done across different use scenarios and vendors below.

He also points to some of the challenges of implementing correct terminology in NMT models, where the system controls are just beginning to be understood. Patents are a domain where there is a great need for terminology work and is also a domain that has a huge vocabulary, which is supposedly a weakness of NMT. However, given that the WIPO is using NMT for their Japanese and Chinese patent translations, and seeing the many options available in the SYSTRAN PNMT framework, I think we may have already reached a point where this is less of an issue when you work with experts. NMT has a significant amount of research that is driving ongoing improvements, thus we should expect to see it continually improve over the next few years.

As is the case with all the new data-driven approaches, we should understand that investments in raising data quality i.e. building terminological consistency and rich, full-featured termbases, will have a long-term productivity yield and allow long-term leverage. Tools and processes that allow this to happen, are often more important in terms of the impact they might have than whether you use RBMT, SMT or NMT.

Currently, the world of machine translation is struck by the impact of deep learning techniques which deal with the matter of optimizing networks between the sentences in a training set for a given language pair. Neural MT (NMT) has made its way from a few publications in 2014 up to the current state, where several practical applications of professional MT services use NMT in a more and more sophisticated way. The method, which is thought to be a revelation in the field of MT for developers and users alike, does hold many advantages compared to classical statistical MT. Besides the improvements like increased fluency, which is obviously a huge step in the direction of human-like translation output, it is well known that NMT has its disadvantages when it comes to the usage of terminology. The efforts made in order to overcome these obstacles show the crucial role that terminology plays in MT customization. At berns language consulting (blc) we are concerned with and focus on terminology management as a basis for language quality optimization processes on a daily basis. We sense that there is a growing interest for MT integration in various fields of businesses, so we took a look into current MT systems and the state of terminology integration in these systems.

Terminology usage is closely tied to the field of domain adaptation, which is a central concept of engine customization in MT. Domain being a special subject area that is identified by a distinctive set of concepts expressed in terms and namings respectively, using terminology is the key to adaptation techniques in the existing MT paradigms. The effort that has to be undertaken to use terminology successfully differs greatly from paradigm to paradigm. Terminology integration can take place at different steps of the MT process and is applied on different stages of MT training.

In rule-based MT (RBMT) specific terminology is handled within separate dictionaries. In applications for private end users, the user can decide to use one or several dictionaries at once. If just one dictionary is used, the term translation depends on the number of target candidates in the respective entry. For example, the target candidates for the German word ‘Fehler’ could be ‘mistake’ or ‘error’ when a general dictionary is used. If the project switches to the use of a specialized software dictionary, the translation for ‘Fehler’ would most likely be ‘bug’ (or ‘error’ if the user wants it to be an additional translation). If more than one dictionary is used, they can be ranked to get translations from the higher ranked dictionaries first if the same source entries are present in more than one of them. Domains can be covered by a specific set of terms gathered from other dictionaries available and by adding own entries to existing dictionaries. For them to function properly with the linguistic rules, it is necessary to choose from a variety of morpho-grammatical features that define the word. While most of the features regarding nouns can be chosen with a little knowledge of case morphology and semantic distinctions, verb entries can be hard to grasp with little knowledge in the verbal semantics.

While RBMT can be sufficient to translate in general domains like medicine, its disadvantages lie in the incapability to adapt to new or fast-changing domains appropriately. If it comes to highly sophisticated systems, tuning the system to a new domain requires trained users and an enormous amount of time. Methods that facilitate fast domain adaption in RBMT are terminology extraction and the import of existing termbases. While these procedures will help the fast integration of new terminology, for the system to get sufficient output quality it is necessary to check new entries for correctness.

Basically, there are 2 ways of integrating terminology in SMT: 1) prior to translation and 2) at runtime. Integration before translation is the preferred way and can be done, again, in two ways: 1) implicitly by using terminology in the writing process of the texts to be used for training and 2) explicitly by adding terms to the training texts after the editing process.

Implicit integration of terminology is the standard case which is simply a more or less controlled byproduct of the editing process before texts are qualified for MT usage. Because SMT systems rely on distributions of source words to target words, it is necessary for the source words and the target words to be used in a consistent manner. If you think of translation projects with multiple authors, the degree of term consistency strongly depends on the usage of tools that are able to check terminology, namely authoring tools that are linked to a termbase. Because the editing process normally follows the train of thought in non-technical text types, there is no control of the word forms used in a text. To take advantage of the terminology at hand, the editing process would need a constant analysis of word form distribution as a basis for completing inflectional paradigms of every term in the text. Clearly, such a process would break the natural editing workflow. In order to achieve compliance with the so-called controlled language in the source texts, authors in highly technical domains can rely on the help of authoring tools together with termbases and an authoring memory. Furthermore, contexts would have to be constructed in order to embed missing word forms of the terms in use. In order to do a fill-up of missing forms, it´s necessary to do an analysis of all the word forms used in the text, which can be done by applying lemmatizers on the text. In the translation step, target terms can be integrated with the help of CAT tools, which is the standard way of doing translations nowadays.

Explicit integration, on the other hand, is done by a transfer of termbase entries into the aligned training texts. This method simply consists of the appendix of terms at the end of the respective file for each language involved in the engine training. Duplication of entries lead to higher probabilities for a given pair of terms, but in order to be sure about the effects of adding terms to the corpus, one would have to do an analysis of term distributions in the corpus, as they will interfere with the newly added terms. The selection of term translation also depends on the probability distributions in the language model. If the term in question was not seen in the language model, it’ll get a very low probability. Another problem with that approach concerns inflection. As termbase entries are nominative singular forms, just transferring them to the corpus may only be sufficient for translation into target languages which are not highly inflected. In order to cover more than the nominative case, word forms have to be added to the corpus until all cells of their inflectional paradigms are filled. Because translation hypotheses (candidate sentences) are based on counts of words in context, for the system to know which word form to choose for a given context, it is necessary to add terms in as many contexts as possible. This is actually done by some MT providers to customize engines for a closed domain.

Whereas terminology integration in the described way is part of the statistical model of the resulting engine, runtime integration of terminology is done by using existing engines together with different termbases. This approach allows for a quick change of target domains to translate in without the need for a complete retraining of the engine. In the Moses system, which in most cases will be the system in mind when SMT is discussed, the runtime approach can be based on the option to read xml-annotated source texts. In order to force term translations based on a termbase, one has to identify inflected word forms corresponding to termbase entries in the source texts first. Preferably this step is backed up by lemmatizer, which derives base forms from inflected forms. Again, it has to be kept in mind, that translating into highly inflected languages, additional morphological processing has to be done.

There are more aspects to domain adaptation in SMT than I discussed here, for example, the combination of training texts with different language models in the training step or the merging of phrase tables of different engines etc. Methods differ from vendor to vendor and depend strongly on the architecture that has proven to be the best for the respective MT service.

Terminology doesn’t come from nothing – it grows, lives and changes with time and depending on the domain it applies to. So, if we speak of domain adaption there is always the adaptation of terminology. There is no domain without a specific terminology, because domains are, in fact, terminological collections (concepts linked to specific namings within a domain) embedded in a distinctive writing style. To meet the requirements of constantly growing and changing namings in everyday domains (think of medicine or politics), MT engines have to be able to use resources which contain up-to-date terminology. While some MT providers view the task of resource gathering as the customer’s contribution to the process of engine customization, others provide a pool of terminology the customer can choose from. Others do extensive work to ensure the optimal integration of terminology in the training data by checking for term consistency and completeness in the training data. One step in the direction of real-time terminology integration was made by the TaaS project, which came into being as a collaboration of Tilde, Kilgray, the Cologne University of Applied Sciences, the University of Sheffield and TAUS. The cloud-based service offers a few handy tools, e.g. for term extraction and bilingual term alignment, which can be used by MT services to dynamically integrate inflected word forms for terms that are unknown to the engine in use. In order to do so, TaaS is linked to online terminology repositories like IATE the EuroTermBank and TAUS. At berns language consulting, we spoke with the leading providers of MT services and most of them agree that up-to-date terminology integration by online services will become more and more important in flexible MT translation workflows.

Summing up term integration methods, what can we do to improve terminology usage and translation quality with MT systems? Apart from the technical aspects that are best left to the respective tool vendors, the MT user can do a lot to optimize MT quality. Terminology management is the first building block in this process. Term extraction methods can help to build mass from scratch when there are no databases yet. As soon as a termbase is created, it should be used together with authoring tools and CAT tools to produce high-quality texts with consistent terminology. Existing texts that do not meet the requirements of consistent terminology should be checked for term variances as a basis for normalization, which aims at the usage of one and the same term for one concept in the text. Another way to improve term translations is by constantly feeding back post-edits of MT translations into the MT system, which could happen in a collaborative way by a number of reviewers or by using a CAT tool together with MT Plug-ins. The process of terminology optimization in translation workflows strongly depends on the systems and interfaces in use, so solutions may change from customer to customer. As systems constantly improve – especially in the field of NMT – we’re looking forward to all the changes and opportunities this brings to translation environments and translation itself.

He also points to some of the challenges of implementing correct terminology in NMT models, where the system controls are just beginning to be understood. Patents are a domain where there is a great need for terminology work and is also a domain that has a huge vocabulary, which is supposedly a weakness of NMT. However, given that the WIPO is using NMT for their Japanese and Chinese patent translations, and seeing the many options available in the SYSTRAN PNMT framework, I think we may have already reached a point where this is less of an issue when you work with experts. NMT has a significant amount of research that is driving ongoing improvements, thus we should expect to see it continually improve over the next few years.

As is the case with all the new data-driven approaches, we should understand that investments in raising data quality i.e. building terminological consistency and rich, full-featured termbases, will have a long-term productivity yield and allow long-term leverage. Tools and processes that allow this to happen, are often more important in terms of the impact they might have than whether you use RBMT, SMT or NMT.

ter·mi·nol·o·gy

ˌtərməˈnäləjē/

noun

noun: terminology; plural noun: terminologies

- the body of terms used with a particular technical application in a subject of study, theory, profession, etc.

"the terminology of semiotics"

synonyms: phraseology, terms, expressions, words, language, lexicon, parlance, vocabulary, wording, nomenclature; More

----------------------------------------------------------

Currently, the world of machine translation is struck by the impact of deep learning techniques which deal with the matter of optimizing networks between the sentences in a training set for a given language pair. Neural MT (NMT) has made its way from a few publications in 2014 up to the current state, where several practical applications of professional MT services use NMT in a more and more sophisticated way. The method, which is thought to be a revelation in the field of MT for developers and users alike, does hold many advantages compared to classical statistical MT. Besides the improvements like increased fluency, which is obviously a huge step in the direction of human-like translation output, it is well known that NMT has its disadvantages when it comes to the usage of terminology. The efforts made in order to overcome these obstacles show the crucial role that terminology plays in MT customization. At berns language consulting (blc) we are concerned with and focus on terminology management as a basis for language quality optimization processes on a daily basis. We sense that there is a growing interest for MT integration in various fields of businesses, so we took a look into current MT systems and the state of terminology integration in these systems.

Domain adaptation and terminology

Terminology usage is closely tied to the field of domain adaptation, which is a central concept of engine customization in MT. Domain being a special subject area that is identified by a distinctive set of concepts expressed in terms and namings respectively, using terminology is the key to adaptation techniques in the existing MT paradigms. The effort that has to be undertaken to use terminology successfully differs greatly from paradigm to paradigm. Terminology integration can take place at different steps of the MT process and is applied on different stages of MT training.

Terminology in Rule-Based MT

In rule-based MT (RBMT) specific terminology is handled within separate dictionaries. In applications for private end users, the user can decide to use one or several dictionaries at once. If just one dictionary is used, the term translation depends on the number of target candidates in the respective entry. For example, the target candidates for the German word ‘Fehler’ could be ‘mistake’ or ‘error’ when a general dictionary is used. If the project switches to the use of a specialized software dictionary, the translation for ‘Fehler’ would most likely be ‘bug’ (or ‘error’ if the user wants it to be an additional translation). If more than one dictionary is used, they can be ranked to get translations from the higher ranked dictionaries first if the same source entries are present in more than one of them. Domains can be covered by a specific set of terms gathered from other dictionaries available and by adding own entries to existing dictionaries. For them to function properly with the linguistic rules, it is necessary to choose from a variety of morpho-grammatical features that define the word. While most of the features regarding nouns can be chosen with a little knowledge of case morphology and semantic distinctions, verb entries can be hard to grasp with little knowledge in the verbal semantics.

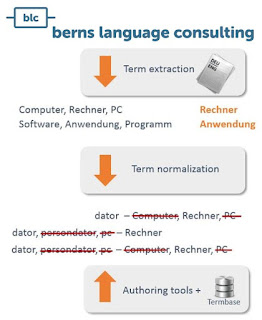

While RBMT can be sufficient to translate in general domains like medicine, its disadvantages lie in the incapability to adapt to new or fast-changing domains appropriately. If it comes to highly sophisticated systems, tuning the system to a new domain requires trained users and an enormous amount of time. Methods that facilitate fast domain adaption in RBMT are terminology extraction and the import of existing termbases. While these procedures will help the fast integration of new terminology, for the system to get sufficient output quality it is necessary to check new entries for correctness.

Terminology in SMT

Basically, there are 2 ways of integrating terminology in SMT: 1) prior to translation and 2) at runtime. Integration before translation is the preferred way and can be done, again, in two ways: 1) implicitly by using terminology in the writing process of the texts to be used for training and 2) explicitly by adding terms to the training texts after the editing process.

Implicit integration of terminology is the standard case which is simply a more or less controlled byproduct of the editing process before texts are qualified for MT usage. Because SMT systems rely on distributions of source words to target words, it is necessary for the source words and the target words to be used in a consistent manner. If you think of translation projects with multiple authors, the degree of term consistency strongly depends on the usage of tools that are able to check terminology, namely authoring tools that are linked to a termbase. Because the editing process normally follows the train of thought in non-technical text types, there is no control of the word forms used in a text. To take advantage of the terminology at hand, the editing process would need a constant analysis of word form distribution as a basis for completing inflectional paradigms of every term in the text. Clearly, such a process would break the natural editing workflow. In order to achieve compliance with the so-called controlled language in the source texts, authors in highly technical domains can rely on the help of authoring tools together with termbases and an authoring memory. Furthermore, contexts would have to be constructed in order to embed missing word forms of the terms in use. In order to do a fill-up of missing forms, it´s necessary to do an analysis of all the word forms used in the text, which can be done by applying lemmatizers on the text. In the translation step, target terms can be integrated with the help of CAT tools, which is the standard way of doing translations nowadays.

Explicit integration, on the other hand, is done by a transfer of termbase entries into the aligned training texts. This method simply consists of the appendix of terms at the end of the respective file for each language involved in the engine training. Duplication of entries lead to higher probabilities for a given pair of terms, but in order to be sure about the effects of adding terms to the corpus, one would have to do an analysis of term distributions in the corpus, as they will interfere with the newly added terms. The selection of term translation also depends on the probability distributions in the language model. If the term in question was not seen in the language model, it’ll get a very low probability. Another problem with that approach concerns inflection. As termbase entries are nominative singular forms, just transferring them to the corpus may only be sufficient for translation into target languages which are not highly inflected. In order to cover more than the nominative case, word forms have to be added to the corpus until all cells of their inflectional paradigms are filled. Because translation hypotheses (candidate sentences) are based on counts of words in context, for the system to know which word form to choose for a given context, it is necessary to add terms in as many contexts as possible. This is actually done by some MT providers to customize engines for a closed domain.

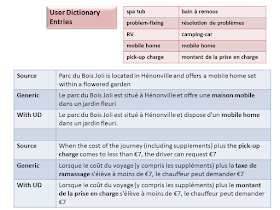

Whereas terminology integration in the described way is part of the statistical model of the resulting engine, runtime integration of terminology is done by using existing engines together with different termbases. This approach allows for a quick change of target domains to translate in without the need for a complete retraining of the engine. In the Moses system, which in most cases will be the system in mind when SMT is discussed, the runtime approach can be based on the option to read xml-annotated source texts. In order to force term translations based on a termbase, one has to identify inflected word forms corresponding to termbase entries in the source texts first. Preferably this step is backed up by lemmatizer, which derives base forms from inflected forms. Again, it has to be kept in mind, that translating into highly inflected languages, additional morphological processing has to be done.

There are more aspects to domain adaptation in SMT than I discussed here, for example, the combination of training texts with different language models in the training step or the merging of phrase tables of different engines etc. Methods differ from vendor to vendor and depend strongly on the architecture that has proven to be the best for the respective MT service.

Terminology Resources

Terminology doesn’t come from nothing – it grows, lives and changes with time and depending on the domain it applies to. So, if we speak of domain adaption there is always the adaptation of terminology. There is no domain without a specific terminology, because domains are, in fact, terminological collections (concepts linked to specific namings within a domain) embedded in a distinctive writing style. To meet the requirements of constantly growing and changing namings in everyday domains (think of medicine or politics), MT engines have to be able to use resources which contain up-to-date terminology. While some MT providers view the task of resource gathering as the customer’s contribution to the process of engine customization, others provide a pool of terminology the customer can choose from. Others do extensive work to ensure the optimal integration of terminology in the training data by checking for term consistency and completeness in the training data. One step in the direction of real-time terminology integration was made by the TaaS project, which came into being as a collaboration of Tilde, Kilgray, the Cologne University of Applied Sciences, the University of Sheffield and TAUS. The cloud-based service offers a few handy tools, e.g. for term extraction and bilingual term alignment, which can be used by MT services to dynamically integrate inflected word forms for terms that are unknown to the engine in use. In order to do so, TaaS is linked to online terminology repositories like IATE the EuroTermBank and TAUS. At berns language consulting, we spoke with the leading providers of MT services and most of them agree that up-to-date terminology integration by online services will become more and more important in flexible MT translation workflows.

Quality improvements – what can MT users do?

Summing up term integration methods, what can we do to improve terminology usage and translation quality with MT systems? Apart from the technical aspects that are best left to the respective tool vendors, the MT user can do a lot to optimize MT quality. Terminology management is the first building block in this process. Term extraction methods can help to build mass from scratch when there are no databases yet. As soon as a termbase is created, it should be used together with authoring tools and CAT tools to produce high-quality texts with consistent terminology. Existing texts that do not meet the requirements of consistent terminology should be checked for term variances as a basis for normalization, which aims at the usage of one and the same term for one concept in the text. Another way to improve term translations is by constantly feeding back post-edits of MT translations into the MT system, which could happen in a collaborative way by a number of reviewers or by using a CAT tool together with MT Plug-ins. The process of terminology optimization in translation workflows strongly depends on the systems and interfaces in use, so solutions may change from customer to customer. As systems constantly improve – especially in the field of NMT – we’re looking forward to all the changes and opportunities this brings to translation environments and translation itself.

======================

Christian Eisold has a background in computational linguistics and is a consultant at berns language consulting since 2016.

At blc he supports customers with translation processes, which involves terminology management, language quality assurance and MT evaluation.