This is a guest post by Aaron Schliem that challenges industry research, and also questions some of the presumption that MT is the only way forward. He also has some well-founded doubts about the imminent demise of many small LSPs which is clearly articulated in this post. I am reprinting the original post with his permission.

One of the myths that continue to propagate in the business translation industry, is that as long as you "use MT" you are relatively well positioned for the future. I, like Aaron, have serious doubts about such a belief. MT ONLY WORKS TO STRATEGIC ADVANTAGE, IF YOU DO IT WELL. Building some kind of a Moses and/or OpenNMT system for face value, in most cases is not necessarily doing MT well. When one does not do something well, it is easy for others who do this same thing well to displace you. At this point in time, I am especially wary of most DIY (Do It Yourself) MT systems built by LSPs. There are a few who have good systems, but they are the exception rather than the rule. I have repeatedly stated in this blog that developing "meaningful" MT competence takes years and new kinds of skills that few LSPs have. Neural MT, in particular, is changing so fast and evolving so rapidly that many academics themselves, are having difficulty keeping up with emerging changes. The odds of LSPs keeping up with these changes is even more remote and one can almost be certain that any self-built system is going to be sub-optimal. The basic reference guideline to use is the quality that DeepL, Bing and Google deliver with no effort whatsover.

Aaron asks "What about the water pipes, you ask? Who will own those – Welocalize, Microsoft, Google?" We have seen (in my comments) how clueless Rory of LIOX (a supposed "giant" of Localization) has been about MT. Even in 2017, he seems not to understand that while he slept at the helm, several faster boats sailed quickly by and now do 99% of the translation done on the planet. Yet he remains unaware. It is my opinion that Microsoft, DeepL, Baidu, and Google will own the pipelines, but those LSPs that clearly add-value and provide meaningful differentiation while they build really great MT systems (with expert assistance) ALSO have a bright future. I would expect that many of these will not be the largest LSPs, and these agencies could quite possibly restructure the balance of power by delivering real value rather than just being larger.

I have also added an interesting comment that was triggered by this post so that it remains intact with the main body of the post.

What does it say about the localization industry when key players in the industry feel the need to apply rather loose analytical criteria in reaching clearly self-serving conclusions?

As I’ve stated in a previous post, it is disappointing to see that many in the localization industry equate globalization with technology-enabled translation. In the drive to keep pace with the rapid proliferation of internet content, larger Language Service Providers (LSPs) have made important technology investments in machine translation (MT), content management system (CMS) connectors, APIs and the like. It is perfectly logical to publicize the value of these technologies, for indeed they certainly can be implemented to assist globalizing companies in more effectively managing their multilingual output. However, in the past few weeks, I’ve seen three examples of important industry voices offering bold but empty claims that implicitly make a case for technology investment, using language that obfuscates or conveniently repositions what the underlying data actually say. This sort of marketing does not honor the real value of localization industry tech. Instead, it attempts to support the status quo by any means necessary, diverting the corporate buyer’s attention away from more holistic approaches to globalization by keeping the focus solely on technology.

What does it say about the localization industry when key players in the industry feel the need to apply rather loose analytical criteria in reaching clearly self-serving conclusions? Kirti Vashee (@kvashee) wrote an interesting article earlier this year about a similar phenomenon in reviewing the Lilt study comparing MT quality. Vashee states, “I think it might not be over-reaching to say that this effort is neither fair nor balanced, except in the way that Fox News is. At the very least, we have gross self-interest pretending to be in the public interest.”

In the example I discuss below we see more of the same – entrenched self-interest masquerading as industry best practice and inspired prescience.

Common Sense Advisory (@CSA_Research) has long been a powerful and valuable voice in the industry. I’ve subscribed to their advisory reports and have found them to be useful resources. That said, in a recent post, it was clear that CSA seems willing to tailor its conclusions to say what the industry wants to hear. Preaching to the choir may suit CSA’s bottom line, but it certainly does not constitute the kind of rigor one would expect from the industry’s leading source of market analysis. Moreover, they have missed an opportunity to bring to light important trends that are changing the way consumers perceive quality and what kind of future we are moving toward.

Using the tags “Best Practices” and “Business Globalization,” CSA put out a teaser blog post to publicize a recent report designed to arm industry professional with data-driven justifications for capturing more localization budget. First off, the title “Hard Data to Support Global Growth” is misleading. While I do not have access to the full article, the blog post offers no clear mapping of localization investment to better global results. CSA allude to potential growth drivers by pointing out that each full-time localization employee “drives” $2.5 billion in international revenue. However, it seems ludicrous to me that CSA would expect a client-side localization manager to use that nugget of data to convince executive management that her team should be allotted more budget. It should be completely obvious to any observer, localizers and laymen alike, that the $2.5B is not a direct outcome of having localization employees. This is a flagrantly misleading and a useless statistic. To calculate ROI there has to be some causation at play. While a localization employee certainly plays a role in ensuring that global roll-outs happen successfully, there are numerous other actors in the corporations and types of investment that will be necessary to deliver international revenue. That CSA would use such an oversimplified set of calculations and then use verbs like “drive” to exaggerate the impact a single localization employee has on international revenue makes one wonder whether CSA really believes that its customers lack the common sense necessary to see through such a hollow conclusion.

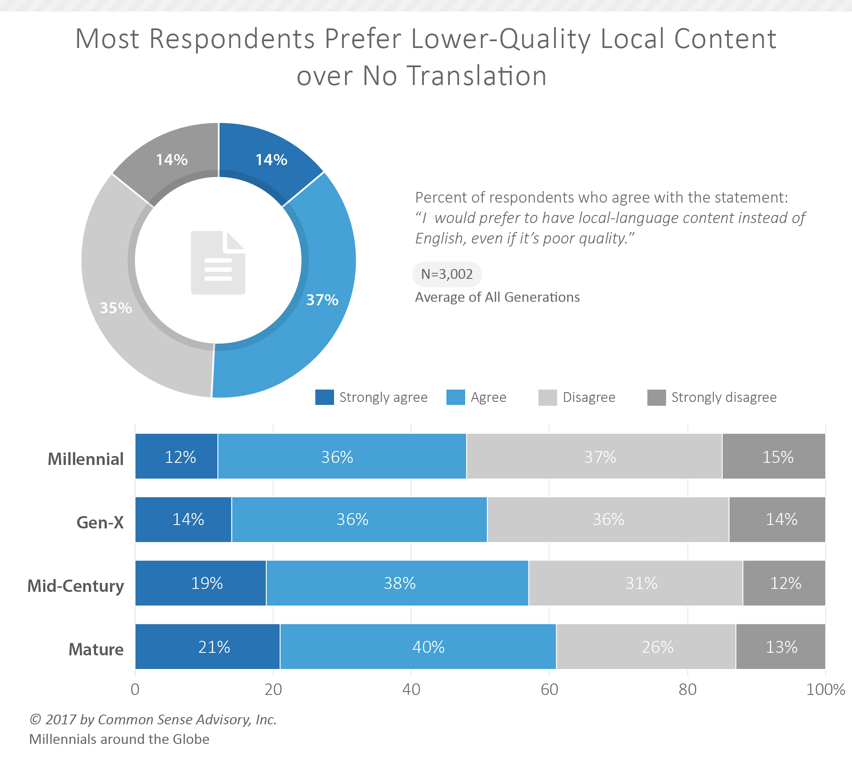

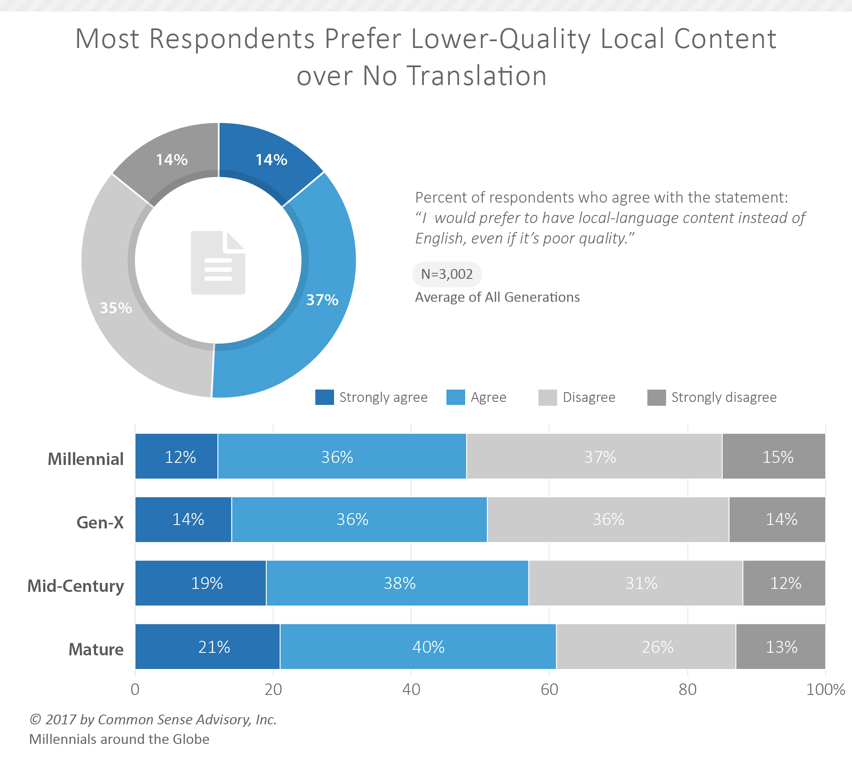

Adding insult to injury, under the subhead, “Sad News for Perfectionists: Some People Prefer Bad Translation to None,” CSA takes a swipe at those in the industry who still value nuanced quality. The idea that “good-enough” is good enough has long been an argument by those who favor MT even when it is not called a strong tactic. Not surprisingly, it is often those with the most to win through MT (MT vendors and larger LSPs with amortizable investments in MT) who make this argument.

The CSA graphic attempts to illustrate that “most respondents” prefer low-quality translation to English. On closer examination one sees that the majority they speak of is a meager 51% majority, a figure that I imagine is within the margin of error for the study (which conveniently has been omitted). Aside from exaggerating this claim, the analysis misses a much more powerful trend. With each successively younger generation that CSA has polled, there is a clear move away from the acceptance of the “something-is-better-than-nothing” content philosophy. Among millennials, the emerging power demographic both by virtue of sheer numbers but more importantly due to the influence they exert in the consumer market, the majority of respondents, in fact, indicate that they disagree with the assertion that poor translation is better than nothing. As millennials continue to demand greater brand authenticity and unabashedly pick winners and losers in our age-of-the-consumer economy, how has CSA neglected to point out this rather obvious and important trend? The only rationale that seems to make sense is that CSA does not want to alienate some segment of its supporters by suggesting that there is even a remote chance that human beings cannot be suckered into accepting subpar language quality, delivered by mediocre MT engines, even when their own graphs illustrate the contrary.

But I digress. Let’s dig into the numbers to see how realistic the claims are, root causes aside. Mr. Straker points to some Common Sense Advisory (CSA) numbers in setting the stage for his analysis. He indicated:

“There are an amazing 18,000 translation companies in 137 countries in the US$38 billion translation industry according to leading research group Common Sense Advisory. 60% have between two and five staff and with average revenue of $1.4m most companies are relatively small.”

Assuming these are accurate metrics, let’s examine Mr. Straker’s bold claim mathematically. If one-third of the 18,000 companies worldwide were to disappear, 6,000 companies would either close shop or would be acquired through M&A activity. Assuming that the industry as a whole is growing and not shrinking, an assertion that CSA’s annual reports clearly support, a grand total of US$8.4B would need to be absorbed by existing or new language services providers (LSPs), if we are to believe in Mr. Straker’s prescience.

Having been a scrappy, small LSP owner myself I can assure you that these 6,000 companies are not going to die out without a fight. Although small LSPs may be weaker financially and technologically than the larger companies in the space, their smaller size makes these LSPs significantly more agile and able to adjust to emerging market conditions. This adaptive advantage is particularly strong when compared to the LSPs who are heavily focused on amortizing their technology investments, betting on a fully automated language services world of the future.

Given that smaller LSPs may be relatively resilient, M&A activity would need to absorb a rather significant chunk of the US$8.4B in revenue. How realistic is that? Given that Lionbridge, the largest company in the industry, is barely a US$500M company (a mere 1.3% of the industry total), I fail to see how M&A activity could accelerate so dramatically that 20% of the throughput for the entire industry could be redistributed among new acquirers. Even if each of the top 100 firms globally were to somehow find equity partners to finance these deals (a nearly impossible order to fill considering the competition for equity and venture dollars in today’s economy), each one would have to acquire (and, perhaps more importantly, integrate) 60 companies a piece, consolidating US$84M of economic activity, across multiple geographies – all within 3.5 years!! Given that a number of the companies listed toward the end of the top 100 list have revenue in the US$8-12M range, it seems unlikely that they will have the wherewithal or, indeed even the motivation, to leverage and pull-off these kinds of deals.

Needless to say, it’s rather disappointing to read the comments of Mr. Straker’s post and observe so many in the industry who are eager to rather blindly to support what seems to be a well-designed publicity stunt. If one looks through the comments on Mr. Straker’s post, one sees many who refute the claims with smart logic and only a few (suspiciously, several come from those who work at MT companies) supporting Mr. Straker’s vision for the future. That said, it’s easy to see why this sort of fear-mongering is useful to a larger LSP that is actively luring small LSPs into selling out for the lowest possible price.

Furthermore, the assertion that smaller companies are not well positioned to differentiate themselves is just bogus. Increasingly, one finds firms in the sector who focus on particular niches (language services for search and discoverability, marketing adaptation, e-learning, multimedia, embedded services, and much more) and finding great success. Now, if the argument is that small companies won’t be able to compete with the localization firms that decide to convert their businesses into the MT-driven word farms, then I agree. But small firms already know that they are not going to win that battle.

I believe a converse argument could be made. If we look to the future (and by future, I mean long-term, not a ridiculous 3.5-year timeframe) I can imagine the industry reaching a point where firms that focus too heavily on MT and hyper-automation may find that they will have squeezed themselves out of the industry.

It might be best to illustrate this with a metaphor I was discussing recently with Kirti Vashee. Let’s imagine that supplying translation is like moving water from the well to homes where it is used. In the early days, all of the different water vendors compete over who has the shiniest buckets, who has the purest water, who can get the water to you fastest. Over time, the vendors who invest in automating the movement of water to homes begin to see great success. People love getting their water faster and cheaper. But pretty soon a new player comes into the market and builds underground pipes to get the water directly from the wells to the homes, benefitting from the work the early investors did to automate and speed the bucket delivery system. With the pipes now in place the water is just a commodity and the early tech investors are out of business.

And what remains? Well, what is left are the vendors who are thinking about what you actually do with the water once you can access it. The smart vendor is the one who is thinking about purpose and application, linguistically and culturally, and not just creating the fastest and cheapest pipeline. I would assert that many of the smaller LSPs are in fact the ones who are focused on nuance, purpose, and specialization. Far from seeing their prospects shrink, I believe it is they who will see a plethora of opportunities arise and who will have the agility to adapt to the new frameworks.

What about the water pipes, you ask? Who will own those – Welocalize, Microsoft, Google? Let’s put that question to people like Kirti who may have more clues as to where the future may lead.

From a LinkedIn conversation triggered by this post that has many more comments:

Yuka Jordan: Speaking from a buyer's viewpoint there underlines a fundamental challenge with localization companies unwillingness or inability to provide answers to clients' problems. My observation has been many are working hard to please their shareholders and senior management. Very few are willing to create a value-add solutions to the ever-growing complex globalization work clients are facing. Granted, many clients have a junior manager to handle all thing localization or complete lack of expertise within their organization, and some clients may appear clueless. It seemed at times, LSP's are taking advantage of the situation to sell what they want to sell. It is the fact that clients do fall for MT technology and lower cost-per-word gimmicks, and make mistakes selecting such an LSP, resulting in the vicious cycle and enabling the industry to remain stagnant. Lack of capability surrounding intelligent data science is prominently evident to some clients whose senior management takes time to analyze and conclude a business solution of their choice. LPS make excuses that clients do not know the industry, and never work on their shortcomings. Hope this article will stir up much-needed industrywide transformation.

Aaron: Thanks for your thoughtful comment Yuka. I think you hit on a key idea here, namely that of value-add. The industry used to think that project management and technology were the value-adds, but as platforms, connectivity, automation improve, these wane in importance. The new value-add will be helping clients to apply language, culture, technology solutions in the right proportions to help them solve their globalization problems. We need to move away from a cookie-cutter approach and from pushing what we want to sell rather than providing what the client needs. Most of all, we need to stop with the low-cost gimmicks. There are certainly places where low-cost strategies make sense, but too often we don't call LSPs out on an overly broad promoting of these strategies, often to the detriment of client outcomes (and after clients have wasted a lot of money on solutions that never delivered what was promised).

Aaron Schliem is the Principal Consultant & Founder of IdioSynch

One of the myths that continue to propagate in the business translation industry, is that as long as you "use MT" you are relatively well positioned for the future. I, like Aaron, have serious doubts about such a belief. MT ONLY WORKS TO STRATEGIC ADVANTAGE, IF YOU DO IT WELL. Building some kind of a Moses and/or OpenNMT system for face value, in most cases is not necessarily doing MT well. When one does not do something well, it is easy for others who do this same thing well to displace you. At this point in time, I am especially wary of most DIY (Do It Yourself) MT systems built by LSPs. There are a few who have good systems, but they are the exception rather than the rule. I have repeatedly stated in this blog that developing "meaningful" MT competence takes years and new kinds of skills that few LSPs have. Neural MT, in particular, is changing so fast and evolving so rapidly that many academics themselves, are having difficulty keeping up with emerging changes. The odds of LSPs keeping up with these changes is even more remote and one can almost be certain that any self-built system is going to be sub-optimal. The basic reference guideline to use is the quality that DeepL, Bing and Google deliver with no effort whatsover.

Aaron asks "What about the water pipes, you ask? Who will own those – Welocalize, Microsoft, Google?" We have seen (in my comments) how clueless Rory of LIOX (a supposed "giant" of Localization) has been about MT. Even in 2017, he seems not to understand that while he slept at the helm, several faster boats sailed quickly by and now do 99% of the translation done on the planet. Yet he remains unaware. It is my opinion that Microsoft, DeepL, Baidu, and Google will own the pipelines, but those LSPs that clearly add-value and provide meaningful differentiation while they build really great MT systems (with expert assistance) ALSO have a bright future. I would expect that many of these will not be the largest LSPs, and these agencies could quite possibly restructure the balance of power by delivering real value rather than just being larger.

I have also added an interesting comment that was triggered by this post so that it remains intact with the main body of the post.

---------

What does it say about the localization industry when key players in the industry feel the need to apply rather loose analytical criteria in reaching clearly self-serving conclusions?

As I’ve stated in a previous post, it is disappointing to see that many in the localization industry equate globalization with technology-enabled translation. In the drive to keep pace with the rapid proliferation of internet content, larger Language Service Providers (LSPs) have made important technology investments in machine translation (MT), content management system (CMS) connectors, APIs and the like. It is perfectly logical to publicize the value of these technologies, for indeed they certainly can be implemented to assist globalizing companies in more effectively managing their multilingual output. However, in the past few weeks, I’ve seen three examples of important industry voices offering bold but empty claims that implicitly make a case for technology investment, using language that obfuscates or conveniently repositions what the underlying data actually say. This sort of marketing does not honor the real value of localization industry tech. Instead, it attempts to support the status quo by any means necessary, diverting the corporate buyer’s attention away from more holistic approaches to globalization by keeping the focus solely on technology.

What does it say about the localization industry when key players in the industry feel the need to apply rather loose analytical criteria in reaching clearly self-serving conclusions? Kirti Vashee (@kvashee) wrote an interesting article earlier this year about a similar phenomenon in reviewing the Lilt study comparing MT quality. Vashee states, “I think it might not be over-reaching to say that this effort is neither fair nor balanced, except in the way that Fox News is. At the very least, we have gross self-interest pretending to be in the public interest.”

In the example I discuss below we see more of the same – entrenched self-interest masquerading as industry best practice and inspired prescience.

Hard data? Or misleading conclusions?

Common Sense Advisory (@CSA_Research) has long been a powerful and valuable voice in the industry. I’ve subscribed to their advisory reports and have found them to be useful resources. That said, in a recent post, it was clear that CSA seems willing to tailor its conclusions to say what the industry wants to hear. Preaching to the choir may suit CSA’s bottom line, but it certainly does not constitute the kind of rigor one would expect from the industry’s leading source of market analysis. Moreover, they have missed an opportunity to bring to light important trends that are changing the way consumers perceive quality and what kind of future we are moving toward.

Using the tags “Best Practices” and “Business Globalization,” CSA put out a teaser blog post to publicize a recent report designed to arm industry professional with data-driven justifications for capturing more localization budget. First off, the title “Hard Data to Support Global Growth” is misleading. While I do not have access to the full article, the blog post offers no clear mapping of localization investment to better global results. CSA allude to potential growth drivers by pointing out that each full-time localization employee “drives” $2.5 billion in international revenue. However, it seems ludicrous to me that CSA would expect a client-side localization manager to use that nugget of data to convince executive management that her team should be allotted more budget. It should be completely obvious to any observer, localizers and laymen alike, that the $2.5B is not a direct outcome of having localization employees. This is a flagrantly misleading and a useless statistic. To calculate ROI there has to be some causation at play. While a localization employee certainly plays a role in ensuring that global roll-outs happen successfully, there are numerous other actors in the corporations and types of investment that will be necessary to deliver international revenue. That CSA would use such an oversimplified set of calculations and then use verbs like “drive” to exaggerate the impact a single localization employee has on international revenue makes one wonder whether CSA really believes that its customers lack the common sense necessary to see through such a hollow conclusion.

Adding insult to injury, under the subhead, “Sad News for Perfectionists: Some People Prefer Bad Translation to None,” CSA takes a swipe at those in the industry who still value nuanced quality. The idea that “good-enough” is good enough has long been an argument by those who favor MT even when it is not called a strong tactic. Not surprisingly, it is often those with the most to win through MT (MT vendors and larger LSPs with amortizable investments in MT) who make this argument.

The CSA graphic attempts to illustrate that “most respondents” prefer low-quality translation to English. On closer examination one sees that the majority they speak of is a meager 51% majority, a figure that I imagine is within the margin of error for the study (which conveniently has been omitted). Aside from exaggerating this claim, the analysis misses a much more powerful trend. With each successively younger generation that CSA has polled, there is a clear move away from the acceptance of the “something-is-better-than-nothing” content philosophy. Among millennials, the emerging power demographic both by virtue of sheer numbers but more importantly due to the influence they exert in the consumer market, the majority of respondents, in fact, indicate that they disagree with the assertion that poor translation is better than nothing. As millennials continue to demand greater brand authenticity and unabashedly pick winners and losers in our age-of-the-consumer economy, how has CSA neglected to point out this rather obvious and important trend? The only rationale that seems to make sense is that CSA does not want to alienate some segment of its supporters by suggesting that there is even a remote chance that human beings cannot be suckered into accepting subpar language quality, delivered by mediocre MT engines, even when their own graphs illustrate the contrary.

“The sky is falling, the sky is falling.”

Although originally published mid-2016, Grant Straker’s article on LinkedIn portending the apocalyptic demise of a third of the companies in the localization industry saw a flurry of activity recently. Mr. Straker (@gstraker), CEO of Straker Translations, bases his menacing projection on three causes: some new movement of content online (not sure I even get this argument, given that dealing with online content has been the bread and butter of the industry – small and large LSPs alike – for quite some time now), easier vendor comparison (making rather broad assumptions that all buyers will shop for the lowest price, period) and MT creating winners and losers when it comes to margins. Ironically, Mr. Straker fears that translators will abandon small LSPs because in order to maintain profitability these losers will try to squeeze talent by demanding lower rates. Ironically, my conversations with translators have revealed quite the contrary. Many seem to prefer working with smaller LSPs precisely BECAUSE they tend not to put translators through the wringer.But I digress. Let’s dig into the numbers to see how realistic the claims are, root causes aside. Mr. Straker points to some Common Sense Advisory (CSA) numbers in setting the stage for his analysis. He indicated:

“There are an amazing 18,000 translation companies in 137 countries in the US$38 billion translation industry according to leading research group Common Sense Advisory. 60% have between two and five staff and with average revenue of $1.4m most companies are relatively small.”

Assuming these are accurate metrics, let’s examine Mr. Straker’s bold claim mathematically. If one-third of the 18,000 companies worldwide were to disappear, 6,000 companies would either close shop or would be acquired through M&A activity. Assuming that the industry as a whole is growing and not shrinking, an assertion that CSA’s annual reports clearly support, a grand total of US$8.4B would need to be absorbed by existing or new language services providers (LSPs), if we are to believe in Mr. Straker’s prescience.

Having been a scrappy, small LSP owner myself I can assure you that these 6,000 companies are not going to die out without a fight. Although small LSPs may be weaker financially and technologically than the larger companies in the space, their smaller size makes these LSPs significantly more agile and able to adjust to emerging market conditions. This adaptive advantage is particularly strong when compared to the LSPs who are heavily focused on amortizing their technology investments, betting on a fully automated language services world of the future.

Given that smaller LSPs may be relatively resilient, M&A activity would need to absorb a rather significant chunk of the US$8.4B in revenue. How realistic is that? Given that Lionbridge, the largest company in the industry, is barely a US$500M company (a mere 1.3% of the industry total), I fail to see how M&A activity could accelerate so dramatically that 20% of the throughput for the entire industry could be redistributed among new acquirers. Even if each of the top 100 firms globally were to somehow find equity partners to finance these deals (a nearly impossible order to fill considering the competition for equity and venture dollars in today’s economy), each one would have to acquire (and, perhaps more importantly, integrate) 60 companies a piece, consolidating US$84M of economic activity, across multiple geographies – all within 3.5 years!! Given that a number of the companies listed toward the end of the top 100 list have revenue in the US$8-12M range, it seems unlikely that they will have the wherewithal or, indeed even the motivation, to leverage and pull-off these kinds of deals.

Needless to say, it’s rather disappointing to read the comments of Mr. Straker’s post and observe so many in the industry who are eager to rather blindly to support what seems to be a well-designed publicity stunt. If one looks through the comments on Mr. Straker’s post, one sees many who refute the claims with smart logic and only a few (suspiciously, several come from those who work at MT companies) supporting Mr. Straker’s vision for the future. That said, it’s easy to see why this sort of fear-mongering is useful to a larger LSP that is actively luring small LSPs into selling out for the lowest possible price.

Furthermore, the assertion that smaller companies are not well positioned to differentiate themselves is just bogus. Increasingly, one finds firms in the sector who focus on particular niches (language services for search and discoverability, marketing adaptation, e-learning, multimedia, embedded services, and much more) and finding great success. Now, if the argument is that small companies won’t be able to compete with the localization firms that decide to convert their businesses into the MT-driven word farms, then I agree. But small firms already know that they are not going to win that battle.

I believe a converse argument could be made. If we look to the future (and by future, I mean long-term, not a ridiculous 3.5-year timeframe) I can imagine the industry reaching a point where firms that focus too heavily on MT and hyper-automation may find that they will have squeezed themselves out of the industry.

It might be best to illustrate this with a metaphor I was discussing recently with Kirti Vashee. Let’s imagine that supplying translation is like moving water from the well to homes where it is used. In the early days, all of the different water vendors compete over who has the shiniest buckets, who has the purest water, who can get the water to you fastest. Over time, the vendors who invest in automating the movement of water to homes begin to see great success. People love getting their water faster and cheaper. But pretty soon a new player comes into the market and builds underground pipes to get the water directly from the wells to the homes, benefitting from the work the early investors did to automate and speed the bucket delivery system. With the pipes now in place the water is just a commodity and the early tech investors are out of business.

And what remains? Well, what is left are the vendors who are thinking about what you actually do with the water once you can access it. The smart vendor is the one who is thinking about purpose and application, linguistically and culturally, and not just creating the fastest and cheapest pipeline. I would assert that many of the smaller LSPs are in fact the ones who are focused on nuance, purpose, and specialization. Far from seeing their prospects shrink, I believe it is they who will see a plethora of opportunities arise and who will have the agility to adapt to the new frameworks.

What about the water pipes, you ask? Who will own those – Welocalize, Microsoft, Google? Let’s put that question to people like Kirti who may have more clues as to where the future may lead.

From a LinkedIn conversation triggered by this post that has many more comments:

Yuka Jordan: Speaking from a buyer's viewpoint there underlines a fundamental challenge with localization companies unwillingness or inability to provide answers to clients' problems. My observation has been many are working hard to please their shareholders and senior management. Very few are willing to create a value-add solutions to the ever-growing complex globalization work clients are facing. Granted, many clients have a junior manager to handle all thing localization or complete lack of expertise within their organization, and some clients may appear clueless. It seemed at times, LSP's are taking advantage of the situation to sell what they want to sell. It is the fact that clients do fall for MT technology and lower cost-per-word gimmicks, and make mistakes selecting such an LSP, resulting in the vicious cycle and enabling the industry to remain stagnant. Lack of capability surrounding intelligent data science is prominently evident to some clients whose senior management takes time to analyze and conclude a business solution of their choice. LPS make excuses that clients do not know the industry, and never work on their shortcomings. Hope this article will stir up much-needed industrywide transformation.

Aaron: Thanks for your thoughtful comment Yuka. I think you hit on a key idea here, namely that of value-add. The industry used to think that project management and technology were the value-adds, but as platforms, connectivity, automation improve, these wane in importance. The new value-add will be helping clients to apply language, culture, technology solutions in the right proportions to help them solve their globalization problems. We need to move away from a cookie-cutter approach and from pushing what we want to sell rather than providing what the client needs. Most of all, we need to stop with the low-cost gimmicks. There are certainly places where low-cost strategies make sense, but too often we don't call LSPs out on an overly broad promoting of these strategies, often to the detriment of client outcomes (and after clients have wasted a lot of money on solutions that never delivered what was promised).

Aaron Schliem is the Principal Consultant & Founder of IdioSynch

Idiosynch is an advisory firm that shows companies of all sizes how to harness the power of cultural authenticity in their workplace culture and global branding. Aaron acts as a virtual Chief Globalization Officer to evaluate identity and systems and to deliver human-centered strategies for smarter global growth.

A 20-year veteran of the language services industry, Aaron is a serial entrepreneur who launched his first company, Horizon Learning, a Chilean adult second language acquisition firm, in 1996. More recently Aaron helped found and lead Glyph Language Services, where as CEO he positioned the firm as a leader in global communications, cross-cultural learning, and adaptive localization of creative media.

A regular speaker at international conferences and workshops Aaron is a thought leader in fields that range from executive compensation to mobile apps and games. Aaron’s writings have been published in Multilingual Magazine, The Content Wrangler, and The Savvy Client's Guide to Translation Agencies. You can read more about Aaron’s approach and philosophy on his blog at www.idiosynch.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment